Have you ever, either personally or professionally, made an assumption about someone based on your interpretation of their behaviour? Or maybe you have found yourself confused about how someone has reacted to something you’ve said? If you can relate to either of these situations, then you’ve experienced the Ladder of Inference.

What is the Ladder of Inference?

In 1970, organizational psychologist – Chris Argyris – created a model called the Ladder of Inference. Since then, many psychologists and organizational behavioral professionals have used it as a base for their models. Below, we apply learnings from Peter Senge’s The Fifth Discipline, and Roger Schwarz’s The Skilled Facilitator to guide us through deescalating conflict using the Ladder of Inference.

Scenario example

Let’s start with a scenario:

I am hosting a barbecue for some close friends, and this is something I’ve been dearly looking forward to. It’s been months since I’ve been able to see them and I also love to cook. So, I’m excited, and even going to try out a new hamburger recipe. As everyone starts eating their supper, my friend Tony says, “Interesting,” as he takes his first bite of the hamburger.

What is your gut reaction to that? How do you feel about that comment?

Some conclusions you may come to about Tony’s impression of your recipe might include:

- He doesn’t like it

- He’s passive aggressive

- There is something strange about the taste

- He doesn’t think this is what hamburgers should be like

There are a lot of different interpretations of that one word – interesting – and we’re going to explore that deeper.

Humans are hardwired to create meaning, so your brain is constantly trying to figure out the meaning of all the situations and things that go on around you. If you don’t have an opportunity to explain what you’ve said or done, then people will infer or make their own meanings. People make sense of the world around them by using the Ladder of Inference.

Climbing the ladder to observe and select information

In the image to the right, we have a modified ladder – not the one that you would typically find from that 1970 version. However, when Tony at this barbecue took a bite of the hamburger and said, “Interesting,” you used that ladder to try and make sense of what he was saying.

This ladder is made up of four main parts:

- The pool of observable information at the base of the ladder

- The information you observe and select at the first rung

- The meaning you create from your information at the second rung

- Your response to the information at the third rung

With every new situation, the first step is that you observe something and select a piece of information. The second thing that you do is make meaning from your observation. Steps one and two typically go hand-in-hand and can occur quite quickly; as you observe something, you may almost automatically assign a meaning to it. The third step of the ladder is choosing how to respond, or if you will respond to the situation. While this ladder may seem fairly simple, it’s much more complex when we start putting it into practice and it can be complicated, difficult, and even a bit challenging at times.

One of the problems with a ladder is that there’s only room for one person and their meaning of a situation at the top of that ladder. If you don’t stop to check your observations or the meaning that you made at those first two steps, you won’t truly be able to understand someone else’s perspective or behaviour. The good news is the rungs go both ways, so as easily as you were able to climb up the ladder, you’re also able to climb back down. This is important when it comes to working with teams and deescalating conflict.

The ladder of inference in the workplace

Whether in your personal or professional life, working with people can get messy because people are complicated and complex creatures. Miscommunication and conflict sometimes arise in groups, especially in new or unfamiliar situations or roles.

According to the CPP Global Human Capital Report (2008), 49% of all recorded workplace conflicts were the result of clashing personalities. However, some research also shows that companies that support a collaborative environment are more likely to have high-performing teams. When you have a collaborative culture, it can possibly result in higher engagement levels, lower stress levels, and higher success rates. If you are able to decrease the conflict and increase collaboration within an organization, you can have a significant impact on the employees’ and overall company’s successes.

Workplace conflict is expensive: according to the CPP report mentioned above, approximately $359 billion in paid hours, or the equivalent of 385 million working days, are lost each year to workplace conflict. Similarly, 362.5 million working days are lost due to conflict in the UK each year. Regardless of where you live or what you do, unresolved conflict at work can have detrimental effects. If you’re able to change a team’s mindset, you can work towards changing that team’s culture. When we talk about mindset, it’s really about the set of values and behaviours that people work from, and that can have an impact on how people work together.

Unilateral control versus mutual learning mindsets

According to Roger Schwarz’s The Skilled Facilitator, there are two prevalent opposing mindsets that people can operate from.

The unilateral control mindset is the “my way is the right way,” or “my way is the highway” mindset. There is no room for other people to share their opinions and you’re typically attempting to make other people see that you’re right.

The mutual learning mindset, however, is much more collaborative. It recognizes that every team member will have a piece of the puzzle to contribute, that you’re smarter together, and that everyone benefits from each person sharing their thoughts. The mutual learning mindset works hand-in-hand with the Ladder of Inference, and when you engage a mutual learning, you’re seeking knowledge that will result in action. The goal of the mutual learning mindset is to create trust and understanding between individuals and groups.

Unfortunately, when many of us are stressed, threatened, or embarrassed, we default to the unilateral control mindset. So how can we work away from that?

If we know that our default is to go into that unilateral mindset while under stress, the next step is to learn to lower your ladder and move toward the mutual learning mindset instead. This requires some self-reflection and openness to an alternate explanation than the one you have invented. You don’t have to be naïve about the situation but approach it with more kindness and generosity and use curiosity to guide your questioning as you try to learn more.

Climbing back down the ladder

Thinking back to our backyard barbecue example, many of us climbed the ladder and made a negative association with the word “interesting.” It happens to us all, but now that you are more familiar with the signs, you may begin to recognize it in your daily life more often.

Now that we have some tools to recognize when we’ve climbed the ladder, it’s time to focus on how to climb back down. Learning to ask some genuine questions is a useful method to help you learn more about the situation and information and to better understand what’s going on. Asking genuine questions can help us obtain that alternate meeting and explanation, which can ultimately help bring that conflict down.

Asking genuine questions

Only genuine questions can help reduce defensive behaviour, but it’s important to note that not all questions are genuine. A genuine question is one that aims to learn something new or gather new information. A non-genuine question is one that is rhetorical or asked with a certain answer in mind. A non-genuine question might be: “Why don’t you just try it my way and see how it works out?” which isn’t genuine because you have an implicit view embedded within the question. In contrast, a genuine question could be, “What kind of problems do you think might occur if we were to try it the way I’m suggesting?”

People are smart, and they can tell the difference between genuine and non-genuine questions. If people think that you are trying to urge them in a direction with your questions, they may get more defensive.

There are three questions you can ask yourself to help determine if your question is genuine:

- Do I already know the answer to my question?

- Am I asking the question to see if people will give the right answer?

- Am I asking the question to make a point?

If you can answer yes to any of these three points, your question isn’t genuine.

Luckily, with practice, you’ll feel confident asking those genuine questions. To get you started, we’ve included some tips below.

Genuine questions aim to create shared understanding. Questions like, “Can you tell me more about that?” “How do you see that?” and “What do you think?” can get you started with practicing how to ask these genuine questions.

Click here to download the Genuine Questions Worksheet

Deescalating conflict

Let’s go back to that first scenario that we went through at the start with Tony and the hamburger. Based on what we know, what would be the directly observable behaviour that you see from the situation?

- Tony took a bite and said, “Interesting”

- Did he have a facial expression or tone of voice?

- Any other body language?

- What was he looking at?

- What are other people doing?

- Does he take another bite?

- Does he finish it?

You may recall that step two is where we attach the meaning to observed behaviour, and steps one and two happen very closely together. Whether you attached a positive or negative meaning to what you observed, you have still climbed the ladder without knowing the full story.

The only way to find out what Tony meant when he said, “interesting,” is to decide how to respond to him or if to respond to him, and your response may vary depending on the meaning you attached to your observation. Your response may also depend on your investment in the relationship: if you think this could impact your relationship, you may want to address it to make sure any perceived conflict doesn’t progress. Luckily, asking a few genuine questions can help clear up any misunderstandings.

Reacting versus responding

In order to climb back down the ladder, it is important to respond and not just react to the information you have.

Examples of reactions may include:

- Telling him “I can’t believe you hate my cooking.”

- Withdrawing and thinking, “I can’t believe he said that; my feelings are so hurt. I’m never going to invite him over here again.”

If possible, we want to avoid reacting. Instead, consider some ways you can respond to get more information:

- “Can you tell me more about what you said?”

- “I heard you say, ‘interesting,’ as you started eating. Can you tell me what you meant by that?”

Navigating the ladder of inference: Using what you’ve learned

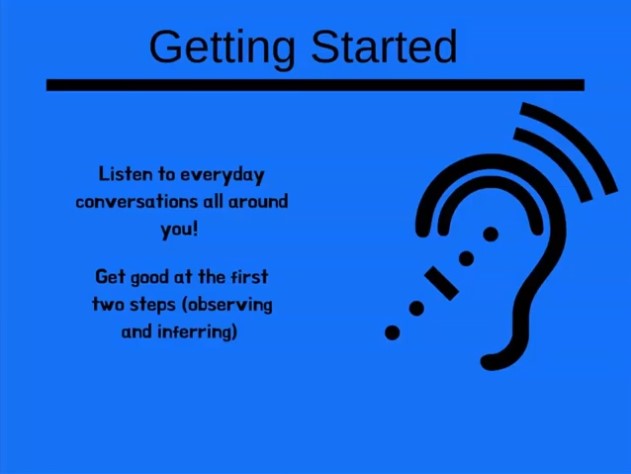

So, what’s next? Now that you’re familiar with the Ladder of Inference, we recommend exploring your day-to-day life for opportunities to listen to the conversations around you to get comfortable with those first two steps of the ladder. Think about the following:

- What did I observe?

- What was the directly observable information?

- What meaning did I make?

Practice is the key to success here. You can only be responsible for your own behaviour and actions, so there is a lot to be said for focusing on self-growth. Once you feel comfortable with the first two steps of the ladder, you can begin to think about how you’re going to respond to situations. Whether in a personal or professional context, your response can be a model for others to learn from on how to deescalate conflict and how to approach situations with generosity, kindness, and a mindset of learning and curiosity.

QI Power Hour is a monthly webinar learning series hosted by the Health Quality Council. We bring together thought leaders from a variety of sectors with an interest in improving health to learn about quality improvement-related topics. For more information on upcoming QI Power Hours, click here.