Nicolas Zulu is an African Leaders of Tomorrow (ALT) scholar from Zambia pursuing a Master of Public Administration degree at the University of Saskatchewan. He worked as a Human Resources Manager in a District Health Office before starting his MPA studies. His long term ambition is to be a leader in the health sector, helping shape policy and strategy to effectively manage the provision of health care to improve the lives of people. The views expressed in this post are those of the author.

I recently interned at the Saskatchewan Health Quality Council (HQC), the agency responsible for the quality of health care in the province of Saskatchewan, to get a better sense of health services in the province and Canada in general. I worked with different areas of the organization and took tours of facilities in both urban and remote areas of the province.

Following my experience at HQC, I identified three areas for possible policy considerations:

1) Remote presence technology to mitigate inequalities in health care

Lack of adequate Human Resources for health is a source of health inequalities in both developed and developing countries. Rural and frontier communities are most in need of health care services due to the high turnover of health care workers. Most counties are improving financial incentives, such as remote retention allowances, to attract health care workers to these communities, and while this helps, it only goes a short way to address this challenge. As a result it is common in many countries that rural communities have higher morbidity and mortality rates relative to urban areas.

The province of Saskatchewan is using remote presence technology to mitigate inadequate access to health services in underserviced communities. Remote presence technology allows physicians to provide real-time medical services to remote communities using electronic mobile devices. The mobile devices are very user-friendly and do not always need a trained health care worker to use them.

Whilst remote presence technology is contingent on factors such as availability of internet services, developing countries have rapidly increased internet access over the past decade and are in a good place to start considering Remote Presence Technology. This calls for being open to this new approach of providing services.

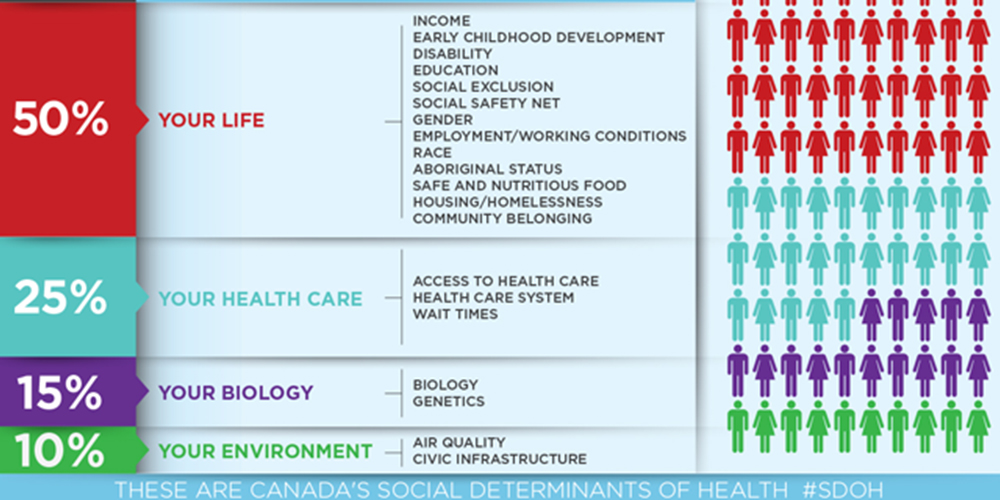

2) Health as an outcome and emphasis on social determinants of health

Health is an outcome of so many societal factors and the interplay of these factors is what shapes the overall health of individuals. Social determinants of health require cross-departmental collaboration, which is often challenging considering that government departments inherently work in silos, with each department or agency having its specific mandate.

The province of Saskatchewan has begun making efforts towards breaking these silos to improve health outcomes. While still in preliminary stages, the province is approaching policy issues through shared goals. The plan is to see the patients’ experience as an outcome of each of the departments’ goals. Understanding all aspects of the patient experience leading up to health care and how each of these can be improved is now seen as the best approach. Not only is this proactive, but also cost-effective in the long run.

3) Long-term care for seniors

While Africa has a relatively young population, with more than half of the population under 25 in some countries, African countries are undergoing demographic transitions. The increasing life expectancy coupled with declining fertility rates suggests that in the next few decades, African countries will have a substantive population of seniors.

It is reasonable to project that this will translate into higher health care costs as well as other costs. Long-term care in some countries may not be considered culturally appropriate, but this is the right time to begin having open discussions about plans for our future seniors.

This post was originally featured on the Canadian Bureau for International Education‘s (CBIE) blog. The CBIE is the national voice advancing Canadian international education by creating and mobilizing expertise, knowledge, opportunity and leadership. View the original post here.