By Dr. Chris Hayes, Chief Medical Information Officer at St. Joseph’s Healthcare in Hamilton and Associate Professor at McMaster University

In health care, the success of any quality improvement project is determined by the perceived value of the change you’re introducing, the work associated with implementing it, and the capacity of the people who will need to make the change. You can boost the chances that your next QI initiative is adopted and sustained by pursuing improvements that don’t add to people’s current workload and that have a high perceived value.

This article will introduce you to the Highly Adoptable Improvement Model and the six key factors you need to pay attention to if you want your next QI project to be a success.

QI Cramming: Trying to do it all, at the same time

How often have you said or heard this, when a new change is introduced at work?

- We don’t have time

- There’s too much change happening already

- We don’t understand why we have to do this

- This doesn’t make sense

- This doesn’t fit with our current processes

Or, have you put a whole bunch of effort into an improvement project that works for a while, but as you move on to the next priority, three months, six months, nine months down the road, the results are waning and not really sustained?

So you try to boost up the process or outcome measures by implementing reminders. Or you provide compliance data comparing one unit or department or one area to another, as a mechanism for reminding people to keep up the hard work. Maybe one of the reasons why we don’t see all of our improvements stick is simply because we’re trying to do too many things.

The crammed QI to-do list

How many of you can relate to this to-do list? The list of improvements that health systems everywhere are trying to make is daunting:

- become more patient- and family-centred

- reduce falls

- bend the cost curve

- improve hand hygiene

- shorten wait times

- implement electronic health records

- prevent pressure ulcers

- reduce reliance on acute care

- accreditation

When you’ve got lots of time, you can do things better, more methodically, take more time, pay more attention to detail.

QI cramming equals shortcuts in our improvement efforts

But when our to-do list is crammed full, we tend to take shortcuts in our improvement efforts. We’re not doing QI the way we used to. We’re putting in some effort, then moving on to the next thing for the sake of trying to get something off our task list.

And what about the people who are impacted by our improvement efforts — the point-of-care providers and managers? Change often comes with added work. During the improvement process, some extra work may be necessary, to provide education and training and to involve people in testing the “intervention.” The crux question though is: What is life like after the new standard or process is in place? There are three possible scenarios:

- The workload has increased

- It has stayed the same

- It has decreased

And the cumulative impact that all of the different changes will have on the workload in our setting is either going to be ideal – because you’ve reduced workload or increased capacity. Or it’s going to be at a new level that is acceptable. Or it will simply be unsustainable. You can’t just keep adding new demands and then expecting people to be able to do that work in the way that it needs to be done.

Perceived value and buy-in for new QI demands

And are the new demands valued? We are not passive recipients of change. We evaluate, seek meaning, and develop feelings toward change. We make decisions about our work and assign a value to things that are presented to us in terms of “perceived value.” We do this in all areas of our life, not just our work in health care. Perceived value has three components:

- There is the emotional aspect: “This change will save lives”

- There is the practical: “I can see myself doing this new practice.”

- And there’s the logical: “That new process makes sense.”

When it comes to quality improvement, perceived value is the willingness or readiness of individuals to adopt change when they believe the outcome of that change will be of value to them, or something of importance to them, such as patients, or colleagues, or their organization, or their career.

Perceived value is actually a marketing term. It refers to the cognitive or subconscious process that we go through when we decide whether we’re going to buy something, make a decision, or adopt a change. So, how can we do a better job in health care of picking and implementing changes that are more likely to stick? By pursuing improvements that are “highly adoptable.”

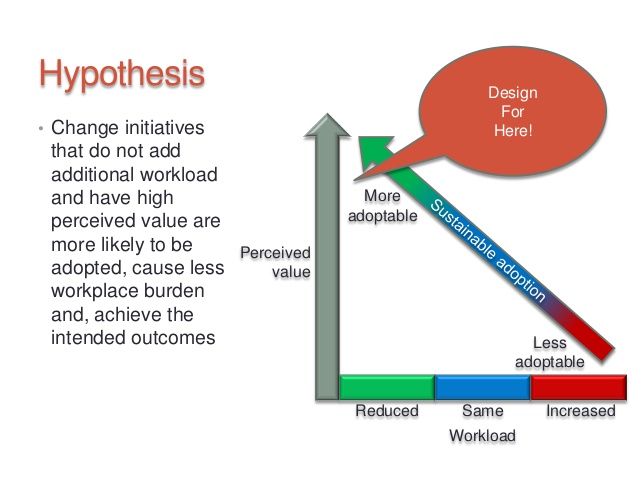

Change initiatives that don’t add to the current workload and have a high perceived value are more likely to be adopted, cause less burden in the workplace, and ultimately achieve their intended outcomes.

The highly adoptable QI Model

The QI sweet spot

You should always design change initiatives to hit the sweet spot at the top left in this graph: high perceived value and decreased workload. That’s because people seek simplicity and value in their lives.

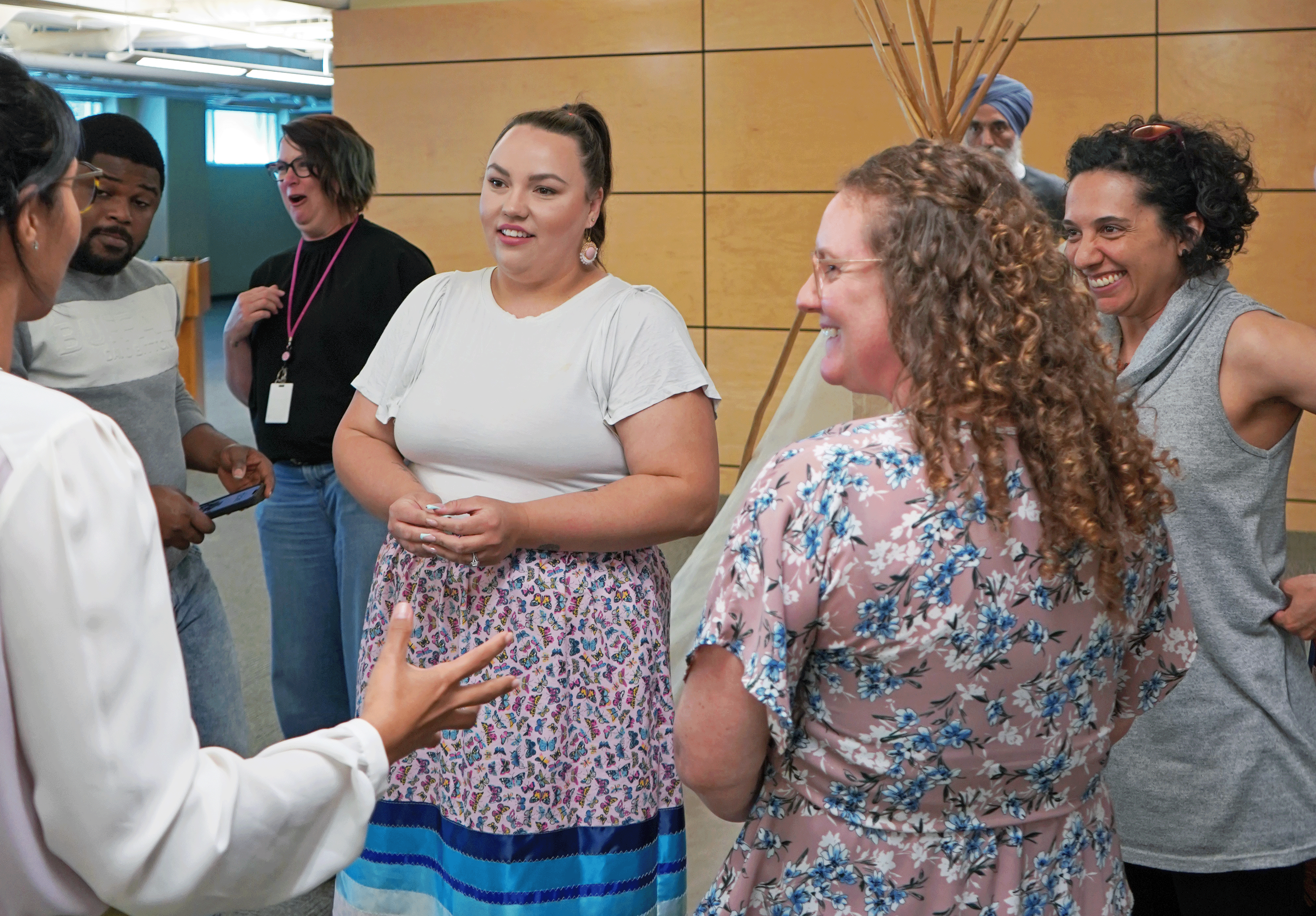

To explore this hypothesis, some colleagues and I dug into the research literature, talked to QI experts, and visited high-performing health care systems. Then we brought together an expert panel to describe what we’d found. The result? The Highly Adoptable Improvement Model.

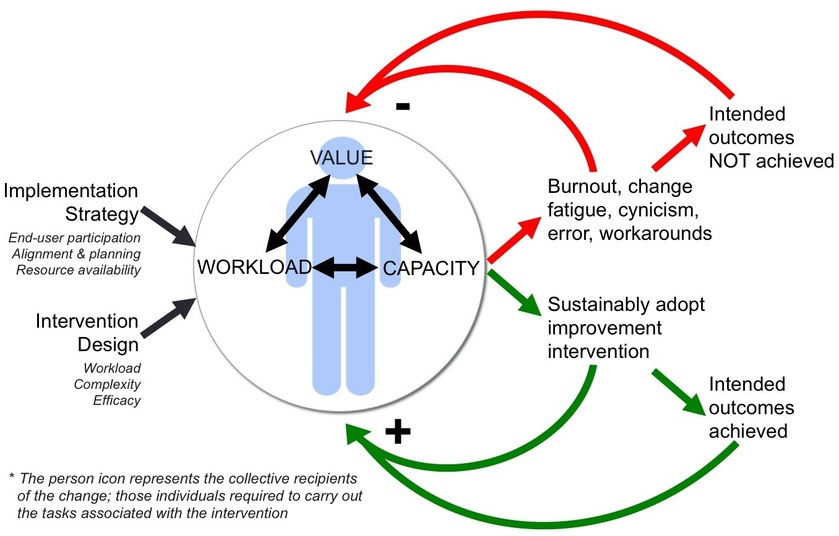

The figure in the middle of the model represents the people who will have to carry out work associated with the change or intervention – this is often point-of-care providers and managers.

The interaction between perceived value, workload, and capacity

The model speaks to the interaction between perceived value, workload, and capacity. If something has high perceived value, we tend to underestimate the work that will be required to achieve it, or overestimate our capacity for achieving it. On the flipside, if people see the perceived value as low, then they will tend to overestimate or reject the workload required to achieve it.

When introducing change, you are in control of two factors that impact on workload:

- Implementation strategy: How are you asking people to make the change? How are you involving them? How are you listening to them? How are you having them become part of the process?

- Intervention design: What are you asking people to do? What are tasks? What does it look like? How do they do it? How do they know how to do it? Do they have the resources?

When you’re increasing the workload and the change has low perceived value (top right of model), this leads to burnout, change fatigue, cynicism, makes people do workarounds, increases likelihood of error, and because people can’t actually do the new work because they don’t want to, or can’t do it, you’re not going to achieve the desired outcome, which in turn has a negative impact, because then people will say: “Wait a minute. You told me this would save lives. We don’t see that. And this work is harder for us. We don’t like this. We don’t want to do this again. And please don’t come back with your next QI initiative.”

When the change you’re introducing decreases workload and has high perceived value or increases capacity, then you increase the likelihood that people will do the task repetitively and sustainably, and if this leads to a positive outcome, then it’s more likely to stick. People will say: “Wow, look what we achieved together, and it wasn’t that hard. I like this quality improvement stuff. Let’s do it again.”

The organizations we studied when we developed our model – Virginia Mason, Thedacare, Kaiser Permanente, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Geisinger, Bellin – tend to live in the bottom right quadrant of the model. People are very willing to participate because they see the benefit and they don’t feel overburdened by it. And their QI culture is therefore high, and the resistance to change is lower.

We started by identifying 72 factors that influence adoption or perceived value. Then within that list, we focused on those factors most closely linked to intervention design. From there, we whittled things down to those domains that are most relevant to QI and are most actionable.

The six factors that determine your improvement’s adoptability

There are six factors that determine how adoptable your QI initiative will be:

1. End-user participation: Are end-user staff/physicians involved in the change?

This one is most important. The more you involve the people that are ultimately going to have to do this work, two things will happen. By having them involved, you’ll get a greater appreciation of their workflow and how things will fit, and you’ll get greater buy-in and an intervention that actually works. The more they’re involved at every stage of change, the more likely you are to generate perceived value and an intervention that works for them and which is likely less work.

2. Alignment and planning: Does the change initiative align with your organization’s and/or team’s goals? Has the rollout been planned effectively?

This one relates more to your implementation strategy. If you think this initiative is important, are you willing to make space for it? Are you going to stop other competing priorities? Are you going to communicate that this is coming so people have time to prepare? If it’s going to be part of a plan, it should be visible, and understood, and hopefully shared — rather than saying: “we’ve identified a gap one month before our accreditation visit and we’ve got to close this.” That has a very different perception at the frontline when it doesn’t appear to be aligned and planned.

3. Resource availability: Are the resources required to implement the change – training, equipment, time, personnel – known and will they be made available?

Do you know what it takes in terms of training, equipment, time, and personnel, for this initiative to work? And are you going to make those available? Resources are often costly and timely, but that doesn’t mean that they’re not required and you may not be able to apply them all, but at least be honest about it: “Look we don’t think we can do this right now but we’re going to try our best.” Acknowledging this builds perceived value and makes it more likely to work.

4. Workload: How much workload – cognitive, physical, time – is associated with the intervention?

How much effort is associated with the intervention? And are you measuring it both objectively and subjectively?

5. Complexity (How complex is the change intervention?

Humans want simplicity and low complexity. They want simple things that are achievable. So, how complex is the intervention? Could it be simpler?

6. Efficacy: What degree of evidence and belief is there that this intervention will lead to the intended outcome?

Finally, what’s the degree of belief and evidence that, if people do this intervention, it will lead to the outcome? There are two sides to this one: First, do I believe that if I apply the evidence that says that if I do something differently I can reduce the incidence of pneumonia among people on ventilators? Then, if I believe that, do I believe that the way you’re asking me to do that I will also achieve those goals? So it’s not just the evidence, but also the way you decided to implement that evidence. Both are important to generating this sense of advocacy that this will work.

Using the tools: Assessment guide and worksheet

We turned these 6 factors into an assessment guide and worksheet.

Use the assessment tool to discuss and assess your proposed change/improvement on each of these 6 domains – scoring the degree of adoptability of your change: the scale ranges from “high risk” on left side to “highly adoptable” on the right. The assessment tool includes detailed descriptions of all points on the scale — High risk, moderate risk, some risk, highly adoptable – to make it easy to understand and use.

If, as you’re scoring your proposed intervention and implementation strategy, you identify that something is moderate risk or high risk, you can use some of the strategies in this toolkit to try and drive it towards high adaptability. Choose interventions with a demonstrated degree of belief. This doesn’t mean they need randomized controlled trials, but there should be some evidence that the way you’ve designed it is going to work: Did it work in other organizations that are similar to yours? And were they using the same methods?

Caring for patients is hard. Change is hard. You can make things easier — and boost your chances of hitting an improvement homerun — by choosing the right intervention and the right implementation strategy.

Now get out there and find your next QI sweet spot. Next steps:

- Watch the “Increase your success rate with QI” QI Power Hour webinar

- Download the Highly Adoptable QI assessment guide and worksheet.